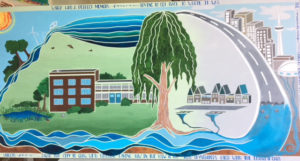

OISE EcoArt Installation 2019 – detail

OISE EcoArt Installation 2019- detail

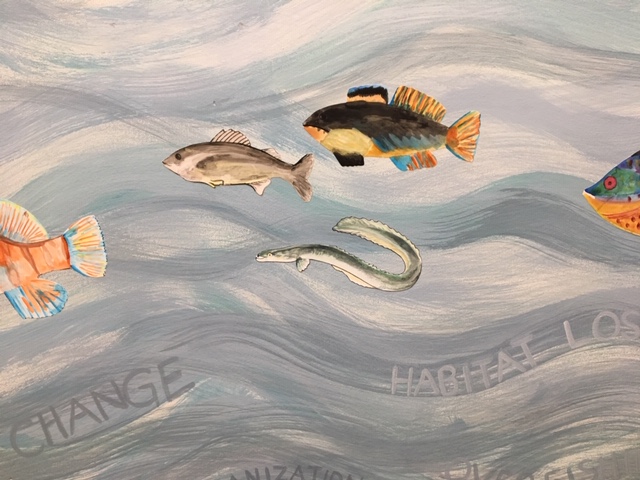

What watershed do you live in? Even though everyone relies on a watershed to ensure our survival, most wouldnãt know how to answer this question. This led to our focus this year on the Great Lakes for our annual eco-art installation at OISE. Framed by an introduction to Ecojustice Education, we aimed to raise awareness of the equity of all living beings in discussions of environmental sustainability, especially ones that remain well-hidden, like fish and other aquatic forms of life. We explored the environmental challenges faced by the lakes and their inhabitants – climate change, loss of habitat, pollution, micro plastics, invasive species, and overfishing are just a few. Despite living in a city that sits on the edge of Lake Ontario, most of us were hard-pressed to name even one fish species in the lake or nearby rivers. So we studied and painted images of fish in the Great Lakes for the installation, which introduced us to species like Rainbow Darter, Rockbass, Northern Redbelly Dace, Atlantic Salmon, Brook Trout, and Yellow Perch. The damage inflicted by humans on these species, as well as others who live in and on the lake, is broad; the ecojustice movement reminds us that injustice spans across locations, species and generations. As part of the creative process we also identified actions we can take in our own lives to lessen the challenges faced by the fish; we can minimize our use of pollutants and plastics; reduce runoff from our yards; and help our students learn about the watersheds they live in through science, math, social studies, and of course, eco-art!

OISE EcoArt Installation 2019

OISE EcoArt Installation 2019 – detail

How do you make art in pristine natural environments without leaving any negative impact on the land? ô This was my challenge as I rafted down the Nahanni River this summer. ô Located in NWT in Canadaãs north, this immense river flows through 5 spectacular canyons, moose meadows, sparkling creeks, a river delta, even a sulphur hot springs. ô It lies on the traditional lands of the Dene people, andô inside the Nahanni National Park,ô ô so ensuring as small an ecological footprint as possible when visiting is critical. ô I continued to explore a technique I began using in the Arctic last summer, that of making nature-based collages. Using the incredible beauty of the geology along the river as inspiration, I arranged rocks, wood and plants into compositions that captured the beauty of this area. ô Once photographed, I returned the components to their original settings to reduce any potential interference with the local ecosystem. This was a type of creative shorthand that allowed me to capture the beauty I was experiencing in a low impact way. ô Certainly it exemplifies the saying, ãTake nothing but photos, leave nothing but footprints,ã and serves as an aesthetic record of my experience in this awe-inspiring part of the world.

How do you make art in pristine natural environments without leaving any negative impact on the land? ô This was my challenge as I rafted down the Nahanni River this summer. ô Located in NWT in Canadaãs north, this immense river flows through 5 spectacular canyons, moose meadows, sparkling creeks, a river delta, even a sulphur hot springs. ô It lies on the traditional lands of the Dene people, andô inside the Nahanni National Park,ô ô so ensuring as small an ecological footprint as possible when visiting is critical. ô I continued to explore a technique I began using in the Arctic last summer, that of making nature-based collages. Using the incredible beauty of the geology along the river as inspiration, I arranged rocks, wood and plants into compositions that captured the beauty of this area. ô Once photographed, I returned the components to their original settings to reduce any potential interference with the local ecosystem. This was a type of creative shorthand that allowed me to capture the beauty I was experiencing in a low impact way. ô Certainly it exemplifies the saying, ãTake nothing but photos, leave nothing but footprints,ã and serves as an aesthetic record of my experience in this awe-inspiring part of the world.

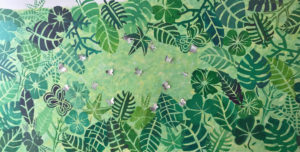

How is environmental art playing out in other parts of the world?ô ô I was lucky to travel to China this last spring, accompanying OISE interns as they taught in five schools in Hangzhou, a city a few hours southwest of Shanghai.ô ô I was impressed with the strong presence for the arts everywhere we travelled, evident in part in the gardens, architecture, public sculpture, and design of public spaces. As part of my visits to these schools, I was able to visit a few art classes, and pleased to see ãlow impactã art-making being taught, inspired by traditional Chinese art forms, like paper-cutting, watercolour, and calligraphy. While I would not consider these forms of eco-art – there was no overt attention to environmental learning – they were supportive of similar tenets.ô ô The watercolours we saw students painting were focused on plants and wildlife; the calligraphy uses natural ink made from charcoal.ô ô A few of the OISE interns also put their learning about eco-art into play. They turned studentsã attention to learning about the plants and insect life in the schoolãs butterfly garden.ô ô Drawing on their experiences working on the last few eco-art installations at OISE,

How is environmental art playing out in other parts of the world?ô ô I was lucky to travel to China this last spring, accompanying OISE interns as they taught in five schools in Hangzhou, a city a few hours southwest of Shanghai.ô ô I was impressed with the strong presence for the arts everywhere we travelled, evident in part in the gardens, architecture, public sculpture, and design of public spaces. As part of my visits to these schools, I was able to visit a few art classes, and pleased to see ãlow impactã art-making being taught, inspired by traditional Chinese art forms, like paper-cutting, watercolour, and calligraphy. While I would not consider these forms of eco-art – there was no overt attention to environmental learning – they were supportive of similar tenets.ô ô The watercolours we saw students painting were focused on plants and wildlife; the calligraphy uses natural ink made from charcoal.ô ô A few of the OISE interns also put their learning about eco-art into play. They turned studentsã attention to learning about the plants and insect life in the schoolãs butterfly garden.ô ô Drawing on their experiences working on the last few eco-art installations at OISE,  they created a beautiful homage to these by combing our butterfly installation from last year with our stencilled plant mural from this year.ô ô I canãt wait to see what these teacher candidates – and our Chinese hosts – accomplish movingô ô forward!

they created a beautiful homage to these by combing our butterfly installation from last year with our stencilled plant mural from this year.ô ô I canãt wait to see what these teacher candidates – and our Chinese hosts – accomplish movingô ô forward!

It must be spring as a new eco-art installation is blooming at OISE!ô ô This year our art team wanted to raise awareness about the importance of native plant species ã their central role in pollination, and their importance in providing healthy habitats for all living things.ô This was one of the ways we are trying to bring engagement with our

It must be spring as a new eco-art installation is blooming at OISE!ô ô This year our art team wanted to raise awareness about the importance of native plant species ã their central role in pollination, and their importance in providing healthy habitats for all living things.ô This was one of the ways we are trying to bring engagement with our  ô

ô  Inspired by a great summer of growing in 2017, we asked graduate students to create large scale stencils of the leaves and flowers of the 30+ native plants in this garden as a way to learn more about them. Making each stencil required careful observation and study of a specific plant – for many of these budding artists this will be the start of a special relationship with that species.ô ô Then a small and dedicated team of students spent two days using the stencils to create a large mural about the garden, developing their artistic skills along the way, and learning how to minimize the environmental footprint of mural painting.ô ô By the number of hours they spent, they were fully immersed in the creative process and the camaraderie of working together towards a common artistic goal. The text, in English, French and Anishinaabemowin, was suggested by the collaborating artists to honour their languages, and reflect the deeper meaning that the garden holds for them.ô Here’s a photo of the completed mural.

Inspired by a great summer of growing in 2017, we asked graduate students to create large scale stencils of the leaves and flowers of the 30+ native plants in this garden as a way to learn more about them. Making each stencil required careful observation and study of a specific plant – for many of these budding artists this will be the start of a special relationship with that species.ô ô Then a small and dedicated team of students spent two days using the stencils to create a large mural about the garden, developing their artistic skills along the way, and learning how to minimize the environmental footprint of mural painting.ô ô By the number of hours they spent, they were fully immersed in the creative process and the camaraderie of working together towards a common artistic goal. The text, in English, French and Anishinaabemowin, was suggested by the collaborating artists to honour their languages, and reflect the deeper meaning that the garden holds for them.ô Here’s a photo of the completed mural.

This is spreading, as artists from all of the arts disciplines are more frequently contributing their unique skills to raising awareness about environmental issues in plays, dance performances, and music videos.ô Here in Toronto we have the Broadleaf Theatre company that specializes in plays with environmental themes; their recent show The Chemical Valley Project tracks the deep challenges of environmental racism and colonialism in relation to Canadaãs petrochemical industry.ô And now thereãs lots of evidence that arts educators around the world are taking up the challenge of doing this work at all levels of education. ô I was happy to work with colleagues in the US and Australia on a chapter in a terrific book called

This is spreading, as artists from all of the arts disciplines are more frequently contributing their unique skills to raising awareness about environmental issues in plays, dance performances, and music videos.ô Here in Toronto we have the Broadleaf Theatre company that specializes in plays with environmental themes; their recent show The Chemical Valley Project tracks the deep challenges of environmental racism and colonialism in relation to Canadaãs petrochemical industry.ô And now thereãs lots of evidence that arts educators around the world are taking up the challenge of doing this work at all levels of education. ô I was happy to work with colleagues in the US and Australia on a chapter in a terrific book called