Are artworks created by First Nations artists a form of environmental art-making?ô Many can be considered as such, based on the imagery and meaning of their works; some draw attention to the natural world, are made with biodegradable materials, celebrate the interconnectedness of all forms of life and/or take an activist stance on environmental issues.ô I was honoured to learn from two artists who are well-known environmental activists here in Ontario – Christi Belcourt (Mûˋtis) and Isaac Murdoch (Ojibwe) (they were keynote speakers this year as part of our national conference in Environmental & Sustainability Education). They are the founders of the Onaman Collective, which focuses on a resurgence of First Nations language and Land-based practices. They have co-designed a series of graphic black and white images that draw on First Nations symbolism to support environmental activism, which they generously share for free with other activists.ô These small-scale, abstracted works sit in contrast to the huge colourful murals created by artist and traditional wisdom keeper Phil Cote (Potawatomi) around the city of Toronto; he leads the Tecumseh Collective. One series of his works is found on the edge of the Humber River, which feature the integral relationships between native riparian wildlife and First Nation peoples. ô All three of these artists take time to work in K-12 schools with children around the GTA and the province, generously sharing their knowledge of and commitment to the Land with the next generation, hopefully leading both Indigenous and settler children to live more lightly on the Earth.

Learning from First Nations’ Artists

Keywords for a Just Recovery

We launched the 14th environmental art installation at OISE in February, and it signals a new approach.ô We havenãt been in our building at OISE for over a year, and we havenãt even been able to install last yearãs installation yet.ô So we thought weãd experiment with a digital installation this year, as everything else has moved online.ô A group of OISE grad students met with me online in the fall to brainstorm ideas for this yearãs project, which had to be simple enough in tools and technique that anyone could contribute an image to this collaborative, community-based artwork. We also felt it had to recognize the pandemic in some way, as this will be an era that will impact our lives for decades to come.ô I think we came up with a creative solution, entitled “Keywords for a Just Recovery.ã The installation was introduced via a webinar, highlighting how the pandemic has brought existing economic, social, and racial injustices to the fore, and how returning to ãnormalã was not an option. We explored the work of artists who have focused on notions of a ãjust recoveryã in recent months ã Jhon Cortes, Ricardo Levins Morales, Corrina Keeling, and Mona Caron, to name just a few, as well as examining the work of some artists who have led the way in working towards social and ecojustice justice for decades, like Krzysztof Wodiczko. OISE community members were invited to contribute an image (with a few keywords) that captures what they believe to be central to a ãjust recoveryã. I’ve really enjoyed working with Ashley Sikorski, one of our talented grad students, on this project (the images above are hers). The work is still in process, and with luck, will result in a digital installation later in the spring, and realized in physical form when our building re-opens.

How will you contribute to a ‘just recovery’?

Taking a Hopeful Approach

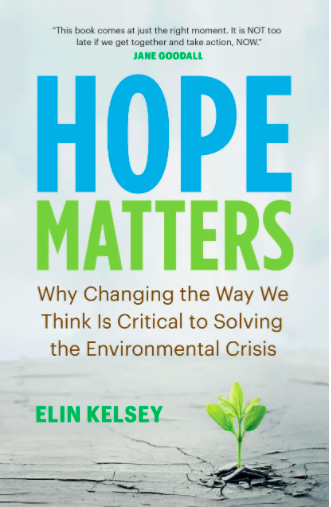

In recent years, environmental educators have been struggling with increasing levels of eco-anxiety in their students, and wondering how to counter this with environmental learning that is less focused on ãdoom and gloomã. The work of Canadian scholar Elin Kelsey has influenced my thinking about this ã she argues that moving away from a legacy of fear and taking a hopeful approach to teaching and learning about the environment and sustainability is necessary, and more productive, in helping students cope with the threatening realities of the climate crisis. One of the strategies she recommends is giving them the tools to take action on environmental issues, to engage them in the process of positive change and develop their sense of agency. In my experience, the arts are a fantastic way to do this. Art-making is a form of visual story-telling, and as Kelsey writes, ãThe stories we tell ourselves shape how we live and what we believe to be possible.ã Artists around the world have taken this to heart ã the explosion in the number of artists focused on environmentally-focused art-making has been extraordinary over the last decade. Each enacts David Orrãs quote ãhope is a verb with its sleeves rolled upã in unique and creative ways. As educators, we need to share the works of these artists with our students, and invite them to utilize all of the arts to shift the narrative, and our thinking, to imagining and enacting a world that is more just, equitable and sustainable.

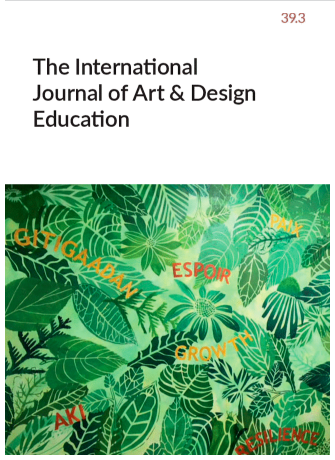

New Study on Eco-Art Ed Pedagogy

Happy to share a new study about eco-art education that our research team finished this fall. Recently published in the Journal of Art and Design Education (2020, vol 39, issue 3), this study explores the impacts of the environmental art installations Iãve been co-creating with students and faculty over the last decade at OISE, found in our walking art gallery. The article is entitled “Conceptualizing Art Education as Environmental Activism in Preservice Teacher Education”, and it draws on methods from arts-based research and qualitative case study in its investigation of the impacts of creating environmental art installations in a community-based, eco-art education program. Our findings support our lived experience that graduate students experienced behavioural and attitudinal shifts towards sustainability after engaging in the processes of creating environmental art; involvement in the program also provided opportunities for building community, engaging multiple domains of learning, modelling sustainable art-making practices, and prompting environmental activism. The results of this study ã along with the cover photo of one of our recent installations – continue to inform a developing pedagogy for environmental art education in higher education settings. My hope is that it inspires others to try eco-art ed in their own institutions.

Eco-learning to E-learning through Nature Journaling

Like so many things over the past few months, my blog writing has been sidelined since the arrival of the pandemic in Canada in March.ô I’ve been working on how to take an active PD series focused on environmental and sustainability education and shift it quickly to e-learning. Weãve been using the Zoom platform to bring EcoSchools teachers together with some success, as we’ve had more teachers involved than ever before. But my next challenge – how to do this with environmental art-making? The limitations have been daunting – the weather outside was wet and chilly, teachers were only able to join online, with no guarantees of specific art materials or tools on hand. But spring always brings with it a sense of excitement and anticipation in a cold climate, so turning our attention to nature-journaling seemed like a viable way to re-connect with other living beings in a time when we were mostly staying inside. I had great models to follow ã check out the amazing work of Clare Walker Leslie, or that of John Muir Laws and Emily Lygren ã artists who have written inspiring books on nature journaling for teachers to follow. I discovered that nature journaling can be framed through the 4Rs ã reconnect with nature, record nature, research nature, and reflect on nature ã and can be easily integrated with math, literacy, geography, and science. Its flexibility can allow for teachers and students to use any art materials at hand, putting their creativity into play as they learn about ecology, biodiversity, and climate change.ô Most importantly, the process of nature journaling can remind us that we are part of nature, not separate from it. If youãd like to experience this webinar, you can find it in the TDSB’s archive.

John Muir Laws & Emily Lygren

Clare Walker Leslie

Creating Garden-based Art in the Cold

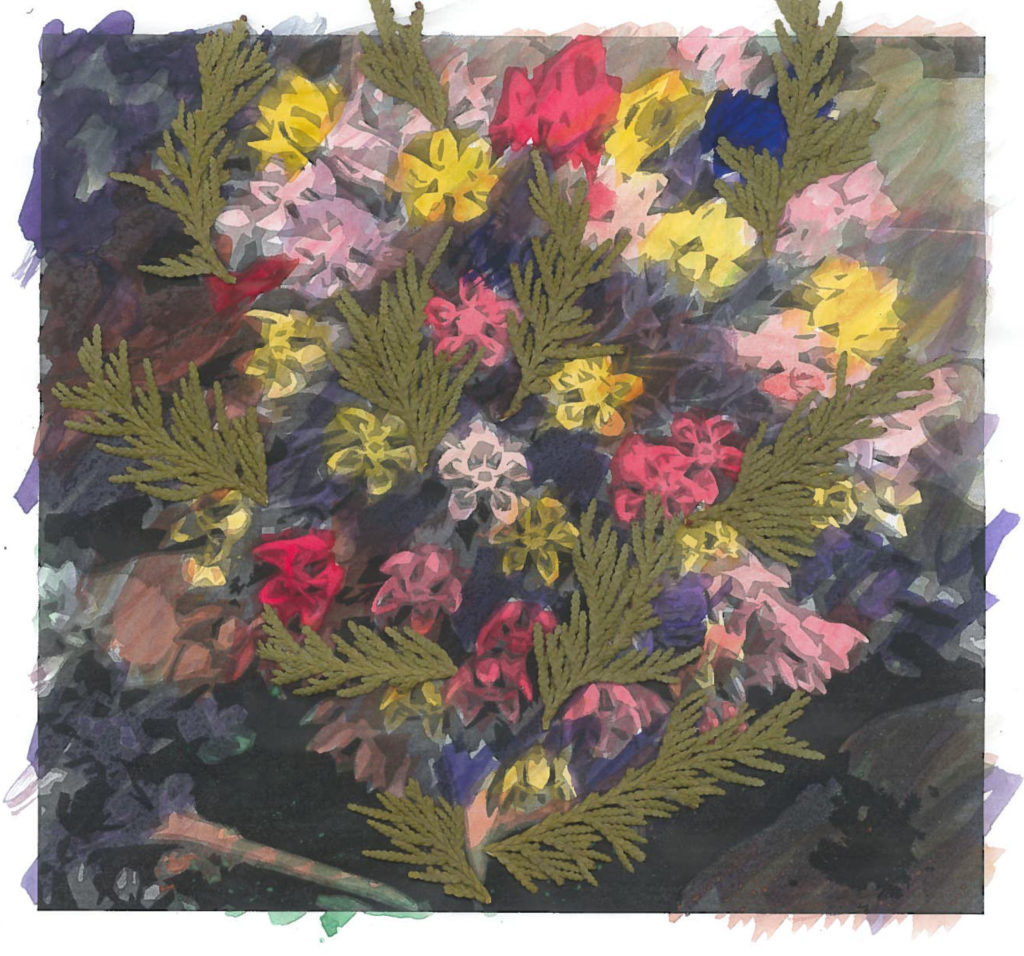

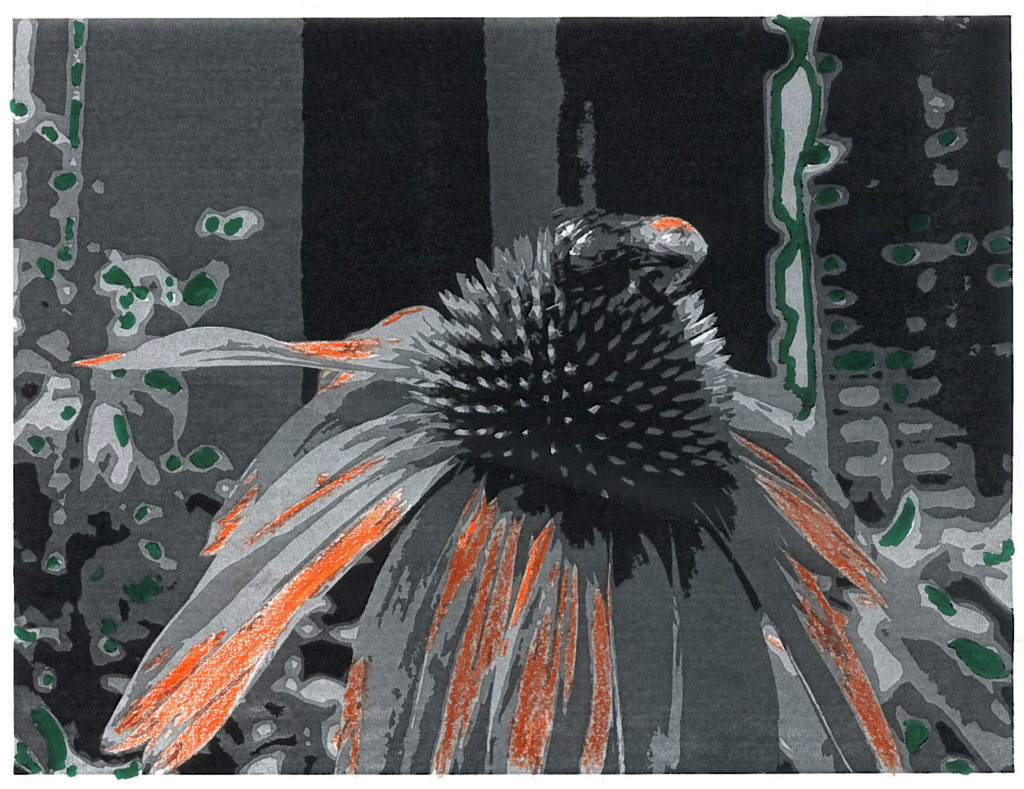

How to do garden-based art making in a cold climate when gardens are still dormant? This was my challenge last April, when the first spring plants were peaking out of the just-thawed soil, as we hosted a research symposium as part of the 2019 AERA conference (one of the worldãs largest education research conferences.) Organized in conjunction with Susan Gerofsky (UBC) and Julia Ostertag, it included five presentations on educational gardens in higher ed institutions across Canada and the US. As the conference theme was on multimodal forms of learning, we decided to include an art-making component, but with no plants in the gardens yet, this proved to be a challenge. I decided to (literally) draw on our large archive of photographs of the plants in the garden instead, along with dried leaves and flowers saved from the previous fall. The forty delegates in attendance were invited to use enlarged black & white photos of the plants in the OISE garden as a starting point to creating their own art. Some added colour with pencil crayons, pastels and watercolours; others cut, folded and ripped the photos, and incorporated dried plant materials. With a variety of entry points, this proved to be a very flexible activity, open to a wide range of skill levels. Many of the delegates expressed their enjoyment of the activity, which enhanced their understanding of the papers presented. Perhaps a new approach to attending academic conferences has been found! See some of the artworks that resulted below.

Growing Garden-based Art

Garden & EcoArt Installed!

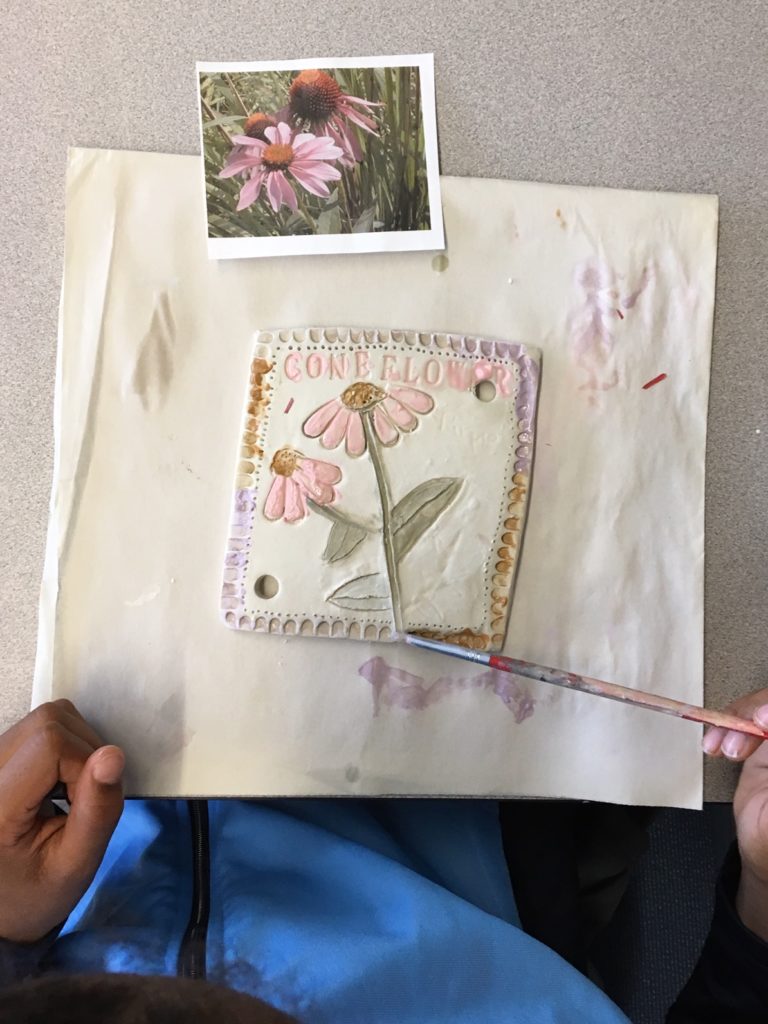

Working on glazing

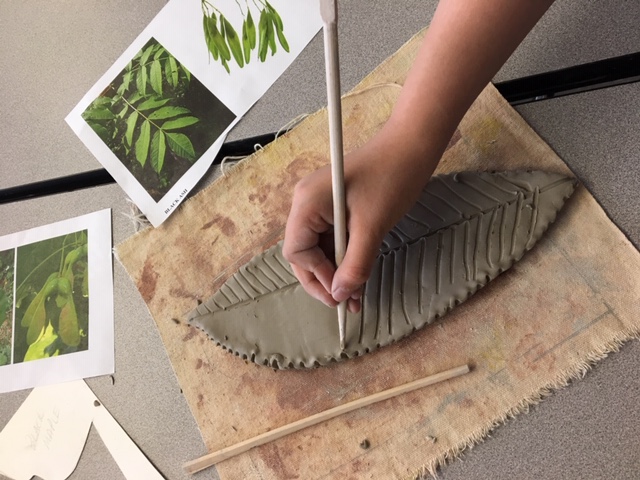

With the return of spring last April, I was happy to work alongside students and teachers at Ryerson Community School (part of the Toronto District School Board) as they began to develop their school garden. They were excited to be working with one of our OISE graduate students, Mimi Ristin, to design and plant their own raised bed gardens filled with native plants, as well as to explore the types of trees in their schoolyard and local park. To help them remember the names of these plants and their benefits, we designed two art installations to share their learning with the school community. Three classes of younger children (grades 2&3) made over-sized clay leaves from native trees, and three more classes (grades 4-6) made clay relief tiles of native flowers. We used a high-fire porcelain clay (cone 6), which had a silky feel and proved to be easy for the children to work with (even though many had never worked with clay before). Rubber letters (such a great tool) were used to press the names of the flowers and trees into the tiles, effectively making these artworks into a visual field guide when installed altogether on the school fence. No doubt that having OISE teacher candidates Clara Hoover and Elena Viazmina help out made the project that much easier! Using natural materials (like clay) and installing outdoors are just two of the strategies for growing art in schoolyards – check out my new article about this in Art Education Journal in July 2019.

Making the clay leaves

Clay leaves on the fence

Casting a Wide Net

OISE EcoArt Installation 2019 – detail

OISE EcoArt Installation 2019- detail

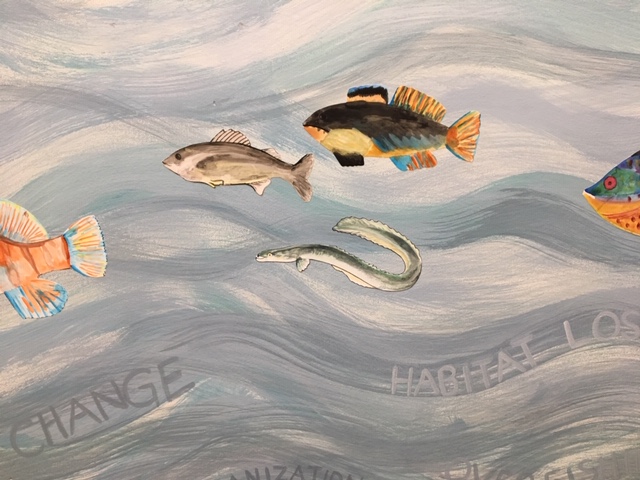

What watershed do you live in? Even though everyone relies on a watershed to ensure our survival, most wouldnãt know how to answer this question. This led to our focus this year on the Great Lakes for our annual eco-art installation at OISE. Framed by an introduction to Ecojustice Education, we aimed to raise awareness of the equity of all living beings in discussions of environmental sustainability, especially ones that remain well-hidden, like fish and other aquatic forms of life. We explored the environmental challenges faced by the lakes and their inhabitants – climate change, loss of habitat, pollution, micro plastics, invasive species, and overfishing are just a few. Despite living in a city that sits on the edge of Lake Ontario, most of us were hard-pressed to name even one fish species in the lake or nearby rivers. So we studied and painted images of fish in the Great Lakes for the installation, which introduced us to species like Rainbow Darter, Rockbass, Northern Redbelly Dace, Atlantic Salmon, Brook Trout, and Yellow Perch. The damage inflicted by humans on these species, as well as others who live in and on the lake, is broad; the ecojustice movement reminds us that injustice spans across locations, species and generations. As part of the creative process we also identified actions we can take in our own lives to lessen the challenges faced by the fish; we can minimize our use of pollutants and plastics; reduce runoff from our yards; and help our students learn about the watersheds they live in through science, math, social studies, and of course, eco-art!

OISE EcoArt Installation 2019

OISE EcoArt Installation 2019 – detail

Aligning the (Eco-Art) Medium with the Message

Remember McLuhan’s famous quote about aligning the medium with the message? He wrote this in the 1960s, well before environmental art-making became so popular, but it’s a good reminder for those of us practicing eco-art ed with learners of all ages. It’s not sufficient to be making art with a sustainability message if the media you use doesn’t align with it. Working with toxic materials like spray paint or oil-based paints subverts the very message we aim to communicate, and demonstrates a “do what I say, not what I do” attitude. Our students are attuned to this type of hypocrisy, and know when we don’t ‘walk the talk’. Art educators need to lead by example, finding ways to share our ideas in low impact, sustainable approaches to art-making. Some make work with their students that is biodegradable (think Andy Goldsworthy as an exemplar); others reuse found materials (Louise Nevelson was an early adopter of this; Tony Cragg also uses it effectively.) I hear of lots of art teachers experimenting with low impact art-making techniques, like gelatin printing and cyanotypes. Others are minimizing their waste and reducing their energy consumption and capturing the waste water from acrylic painting. If you’re looking for ideas on how to proceed, look to the Karen Michel’s book “The Green Guide for Artists” as a great starting point. Consider how can you take the next step in aligning your sustainability message with the media you use in your art classroom.

Growing a Garden-Based Approach to Art Education

The gardens around schools, whether found in the schoolyard or a nearby park, can be a great way to inspire and integrate learning across the curriculum.ô ô I was happy to have this recognized recently by the international Art Education journal, which published ãGrowing a Garden-Based Approach to Art Educationã in their July 2018 issue, and put on of the photos of the article on the cover!ô Co-authored with OISE graduate student (now alumni) Jennifer Sharpe, we aimed to explore the joys of taking art education into the school garden as a way to inform, inspire, and celebrate studentsã creativity. Drawing on the tenets of place-based education and nature-based learning, we presented a case study of a vibrant school garden in Toronto that has been the site of childrenãs artistic exploration for over a decade. We know that when art education is conducted in schoolyards and school gardens, using these spaces as sites of discovery, creativity, meaning-making, and experimentation, children are able to deepen their understanding of the natural and built world, and develop strong connections to the environments in which they live.ô If youãd like to read more, access the article at:ô https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00043125.2018.1465318