Iāve been learning more about regenerative sustainability recently from my colleague John Robinson, who has been a vocal advocate for it at the University of Toronto in recent years (and at UBC for many years before that).Ā This is built on the premise that itās not enough to create communities that are ānet zeroā in terms of their greenhouse gas emissions, but in fact are ānet positiveā by actively contributing to a more sustainable world.Ā John introduced me to this through the Centre for Interactive Research on Sustainability at UBC, (a building he helped design; it sends rain water used to flush toilets in the building back into the sewer cleaner than it arrived).Ā So Iāve been looking for examples of āregenerative art-makingā, and realized that we have two excellent examples of this in permanent installations of this in Toronto.Ā Noel Hardingās ‘Elevated Wetlandsā (1999), recognized by many Torontonians for its prominent position along the DVP, was an early example of this. Using solar pumps, native plants and a recycled plastic substrate, Noel integrated science and art to model how an art installation can contribute to the cleansing of the Don River (known as one of Canadaās most polluted rivers.) Jill Anholt picked up on this two decades later in her design for Sherbourne Common, a small park on Torontoās waterfront.Ā With a similar purpose in mind, Anholtās design uses UV light, native plantings and a mesh screening system to cleanse storm-water run off before it goes into lake Ontario. Both artworks create inspiring, purposeful spaces that model regenerative sustainability in creative ways – we need more like these around the word!

Art as Regenerative Sustainability

Learning from First Nations’ Artists

Are artworks created by First Nations artists a form of environmental art-making?Ā Many can be considered as such, based on the imagery and meaning of their works; some draw attention to the natural world, are made with biodegradable materials, celebrate the interconnectedness of all forms of life and/or take an activist stance on environmental issues.Ā I was honoured to learn from two artists who are well-known environmental activists here in Ontario – Christi Belcourt (MĆ©tis) and Isaac Murdoch (Ojibwe) (they were keynote speakers this year as part of our national conference in Environmental & Sustainability Education). They are the founders of the Onaman Collective, which focuses on a resurgence of First Nations language and Land-based practices. They have co-designed a series of graphic black and white images that draw on First Nations symbolism to support environmental activism, which they generously share for free with other activists.Ā These small-scale, abstracted works sit in contrast to the huge colourful murals created by artist and traditional wisdom keeper Phil Cote (Potawatomi) around the city of Toronto; he leads the Tecumseh Collective. One series of his works is found on the edge of the Humber River, which feature the integral relationships between native riparian wildlife and First Nation peoples. Ā All three of these artists take time to work in K-12 schools with children around the GTA and the province, generously sharing their knowledge of and commitment to the Land with the next generation, hopefully leading both Indigenous and settler children to live more lightly on the Earth.

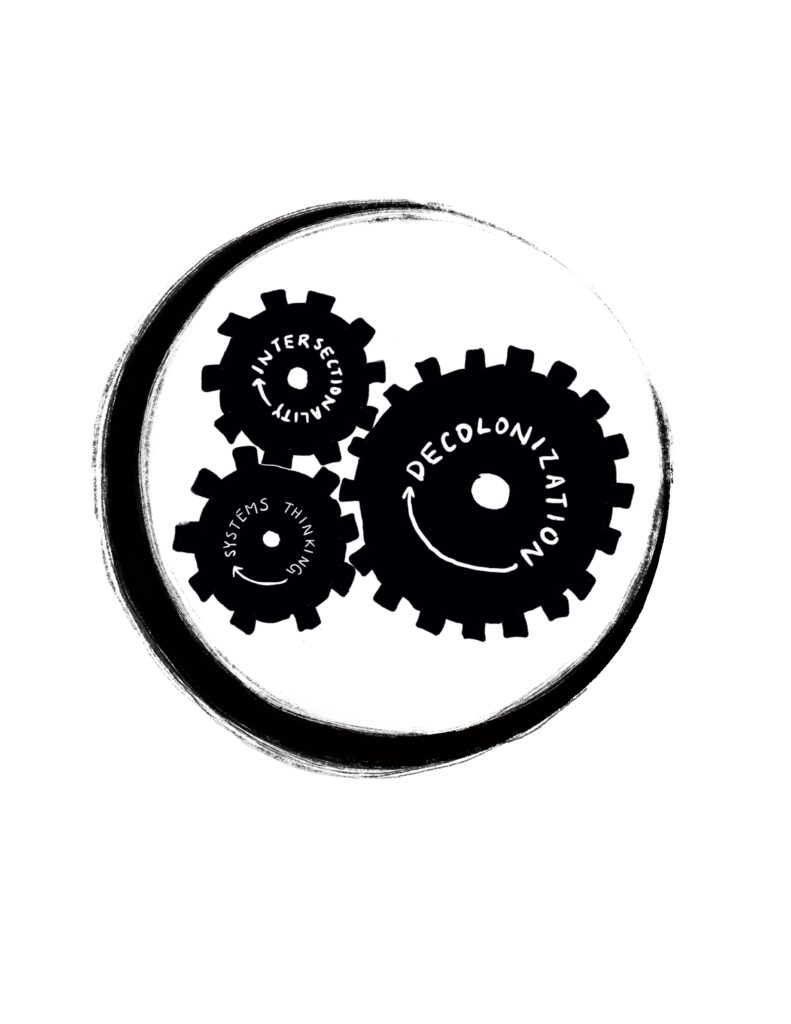

Keywords for a Just Recovery

We launched the 14th environmental art installation at OISE in February, and it signals a new approach.Ā We havenāt been in our building at OISE for over a year, and we havenāt even been able to install last yearās installation yet.Ā So we thought weād experiment with a digital installation this year, as everything else has moved online.Ā A group of OISE grad students met with me online in the fall to brainstorm ideas for this yearās project, which had to be simple enough in tools and technique that anyone could contribute an image to this collaborative, community-based artwork. We also felt it had to recognize the pandemic in some way, as this will be an era that will impact our lives for decades to come.Ā I think we came up with a creative solution, entitled “Keywords for a Just Recovery.ā The installation was introduced via a webinar, highlighting how the pandemic has brought existing economic, social, and racial injustices to the fore, and how returning to ānormalā was not an option. We explored the work of artists who have focused on notions of a ājust recoveryā in recent months ā Jhon Cortes, Ricardo Levins Morales, Corrina Keeling, and Mona Caron, to name just a few, as well as examining the work of some artists who have led the way in working towards social and ecojustice justice for decades, like Krzysztof Wodiczko. OISE community members were invited to contribute an image (with a few keywords) that captures what they believe to be central to a ājust recoveryā. I’ve really enjoyed working with Ashley Sikorski, one of our talented grad students, on this project (the images above are hers). The work is still in process, and with luck, will result in a digital installation later in the spring, and realized in physical form when our building re-opens.

How will you contribute to a ‘just recovery’?

Taking a Hopeful Approach

In recent years, environmental educators have been struggling with increasing levels of eco-anxiety in their students, and wondering how to counter this with environmental learning that is less focused on ādoom and gloomā. The work of Canadian scholar Elin Kelsey has influenced my thinking about this ā she argues that moving away from a legacy of fear and taking a hopeful approach to teaching and learning about the environment and sustainability is necessary, and more productive, in helping students cope with the threatening realities of the climate crisis. One of the strategies she recommends is giving them the tools to take action on environmental issues, to engage them in the process of positive change and develop their sense of agency. In my experience, the arts are a fantastic way to do this. Art-making is a form of visual story-telling, and as Kelsey writes, āThe stories we tell ourselves shape how we live and what we believe to be possible.ā Artists around the world have taken this to heart ā the explosion in the number of artists focused on environmentally-focused art-making has been extraordinary over the last decade. Each enacts David Orrās quote āhope is a verb with its sleeves rolled upā in unique and creative ways. As educators, we need to share the works of these artists with our students, and invite them to utilize all of the arts to shift the narrative, and our thinking, to imagining and enacting a world that is more just, equitable and sustainable.

New Study on Eco-Art Ed Pedagogy

Happy to share a new study about eco-art education that our research team finished this fall. Recently published in the Journal of Art and Design Education (2020, vol 39, issue 3), this study explores the impacts of the environmental art installations Iāve been co-creating with students and faculty over the last decade at OISE, found in our walking art gallery. The article is entitled “Conceptualizing Art Education as Environmental Activism in Preservice Teacher Education”, and it draws on methods from arts-based research and qualitative case study in its investigation of the impacts of creating environmental art installations in a community-based, eco-art education program. Our findings support our lived experience that graduate students experienced behavioural and attitudinal shifts towards sustainability after engaging in the processes of creating environmental art; involvement in the program also provided opportunities for building community, engaging multiple domains of learning, modelling sustainable art-making practices, and prompting environmental activism. The results of this study ā along with the cover photo of one of our recent installations – continue to inform a developing pedagogy for environmental art education in higher education settings. My hope is that it inspires others to try eco-art ed in their own institutions.

Holiday Re-purposing

This time of year always brings me back to a bit of eco-artmaking, even as the season does a deep dive into hyper-consumerism. For the past 6 years, Iāve been re-purposing old Christmas cards into new one, putting my sustainability principles and my creativity into play. In early December each year I think the same thing ā Iām too tired at the end of a busy fall to make handmade cards ā what am I thinking? And then I start to create the image, and then make each card, and it gives me a new sense of energy that carries me into the holidays. The idea is catching on, as a few of my artistic friends have picked up on the idea and are making their own. Hereās examples from years gone by ā such an easy way to show that re-thinking and re-purposing are two of the most important āRās!

Choice-based Approaches to Art Education

What a year this has been! The pandemic has continued to hold me back from blogging, thanks to the seismic shift to online learning and all of it new dimensions. One of my biggest challenges has been how to move my Art Education courses online ā how do I teach basic art techniques to preservice teachers, many of whom havenāt made art since their own time as elementary students? And how do I do that with no access to a common set of art materials or tools? Lots of talking with my artistic friends and fellow art educators made me realize that mailing out a set of basic tools and materials would only add to the carbon footprint of the course, which is the opposite of what Iām trying to teach. Instead, I drew inspiration from Deborah Sickler-Voigtās book Teaching and Learning in Art Education. In it, she promotes the notion of a comprehensive approach to art education, which is student-centred, inclusive, multidisciplinary, and most importantly, choice-based. What if I moved the focus away from technique and put more emphasis on mean-making? What if the tools and materials they used were based on what they had on hand at home, rather than on what I provided? I piloted this approach last spring for the first time, and taught it again this fall, with steadily improving results each time. I saw the same realization grow from week to week that my students are indeed creative beings (just like I have seen in my F2F classes), and that they could make art in lots of different ways, using a wide range of materials and techniques. Letting the ābig ideasā they feel passionate about be at the centre of the creative process ensured their buy-in, and we were all amazed at the incredible variety of artworks that resulted. We used the online app āSeeSawā to share our artworks, ensuring a rich trading of ideas between students. While I still miss learning alongside them in person, giving them more creative latitude and choice are elements Iāll keep in play in this course moving forward.

Eco-learning to E-learning through Nature Journaling

Like so many things over the past few months, my blog writing has been sidelined since the arrival of the pandemic in Canada in March.Ā I’ve been working on how to take an active PD series focused on environmental and sustainability education and shift it quickly to e-learning. Weāve been using the Zoom platform to bring EcoSchools teachers together with some success, as we’ve had more teachers involved than ever before. But my next challenge – how to do this with environmental art-making? The limitations have been daunting – the weather outside was wet and chilly, teachers were only able to join online, with no guarantees of specific art materials or tools on hand. But spring always brings with it a sense of excitement and anticipation in a cold climate, so turning our attention to nature-journaling seemed like a viable way to re-connect with other living beings in a time when we were mostly staying inside. I had great models to follow ā check out the amazing work of Clare Walker Leslie, or that of John Muir Laws and Emily Lygren ā artists who have written inspiring books on nature journaling for teachers to follow. I discovered that nature journaling can be framed through the 4Rs ā reconnect with nature, record nature, research nature, and reflect on nature ā and can be easily integrated with math, literacy, geography, and science. Its flexibility can allow for teachers and students to use any art materials at hand, putting their creativity into play as they learn about ecology, biodiversity, and climate change.Ā Most importantly, the process of nature journaling can remind us that we are part of nature, not separate from it. If youād like to experience this webinar, you can find it in the TDSB’s archive.

John Muir Laws & Emily Lygren

Clare Walker Leslie

Creating Garden-based Art in the Cold

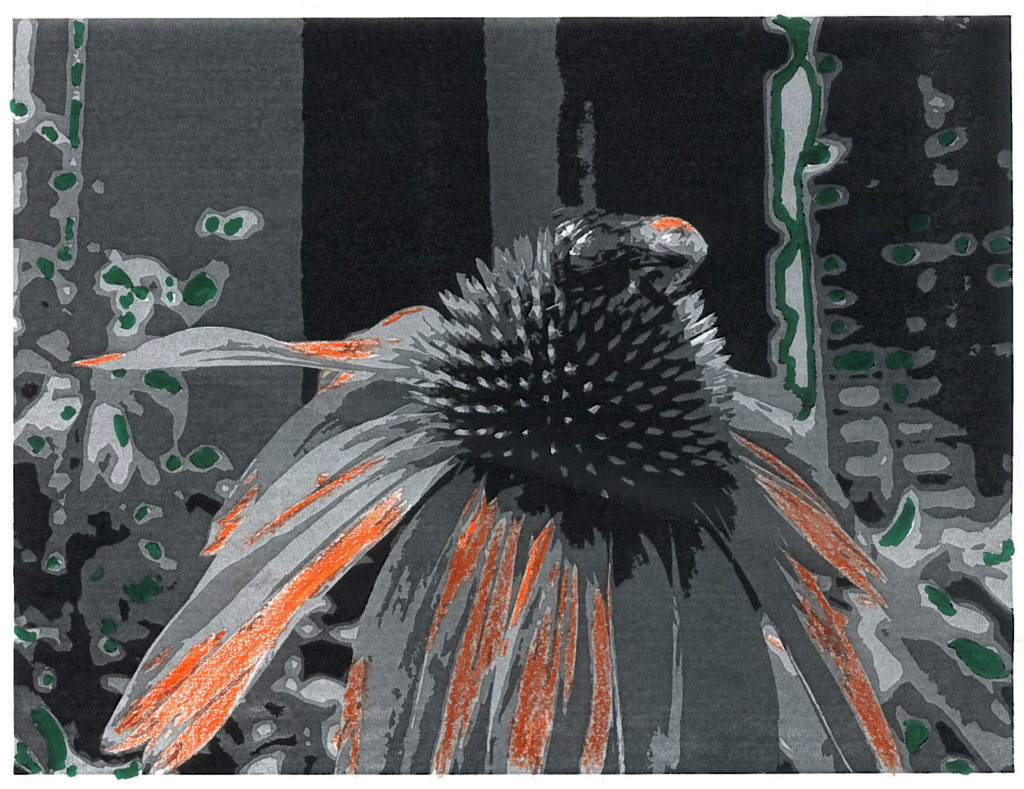

How to do garden-based art making in a cold climate when gardens are still dormant? This was my challenge last April, when the first spring plants were peaking out of the just-thawed soil, as we hosted a research symposium as part of the 2019 AERA conference (one of the worldās largest education research conferences.) Organized in conjunction with Susan Gerofsky (UBC) and Julia Ostertag, it included five presentations on educational gardens in higher ed institutions across Canada and the US. As the conference theme was on multimodal forms of learning, we decided to include an art-making component, but with no plants in the gardens yet, this proved to be a challenge. I decided to (literally) draw on our large archive of photographs of the plants in the garden instead, along with dried leaves and flowers saved from the previous fall. The forty delegates in attendance were invited to use enlarged black & white photos of the plants in the OISE garden as a starting point to creating their own art. Some added colour with pencil crayons, pastels and watercolours; others cut, folded and ripped the photos, and incorporated dried plant materials. With a variety of entry points, this proved to be a very flexible activity, open to a wide range of skill levels. Many of the delegates expressed their enjoyment of the activity, which enhanced their understanding of the papers presented. Perhaps a new approach to attending academic conferences has been found! See some of the artworks that resulted below.

Growing Garden-based Art

Garden & EcoArt Installed!

Working on glazing

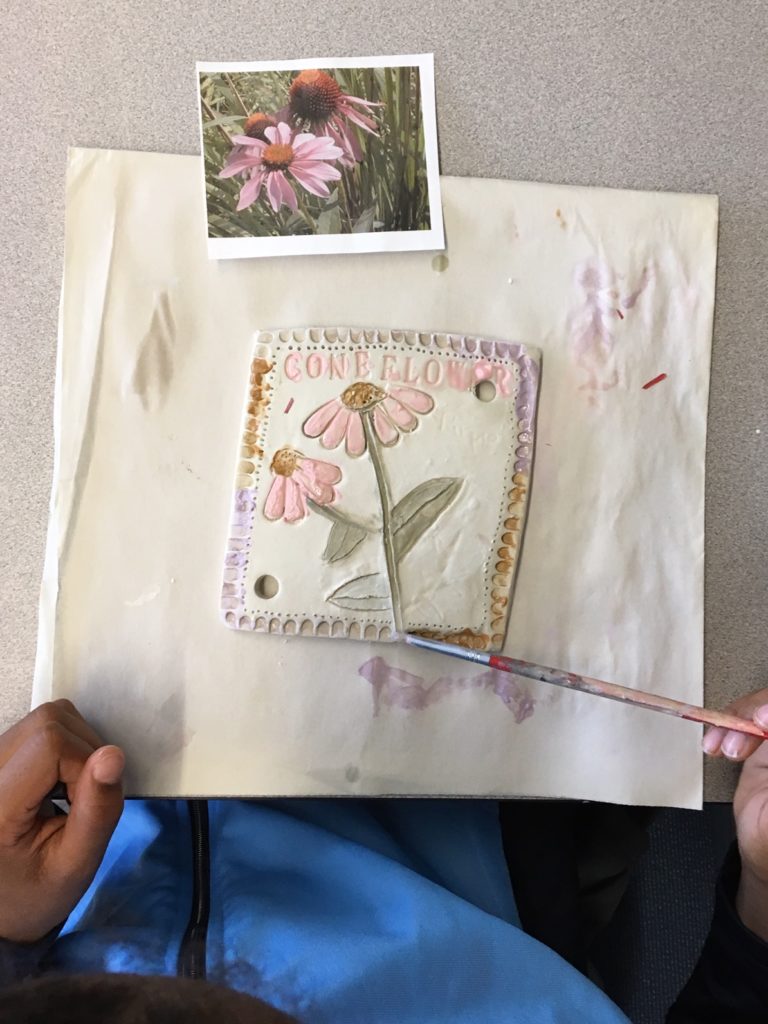

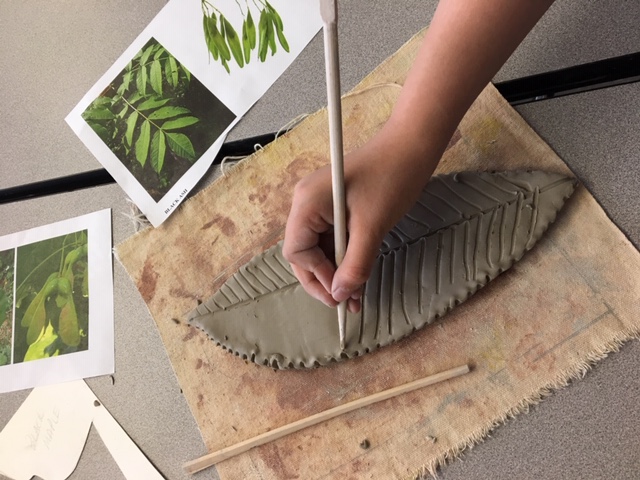

With the return of spring last April, I was happy to work alongside students and teachers at Ryerson Community School (part of the Toronto District School Board) as they began to develop their school garden. They were excited to be working with one of our OISE graduate students, Mimi Ristin, to design and plant their own raised bed gardens filled with native plants, as well as to explore the types of trees in their schoolyard and local park. To help them remember the names of these plants and their benefits, we designed two art installations to share their learning with the school community. Three classes of younger children (grades 2&3) made over-sized clay leaves from native trees, and three more classes (grades 4-6) made clay relief tiles of native flowers. We used a high-fire porcelain clay (cone 6), which had a silky feel and proved to be easy for the children to work with (even though many had never worked with clay before). Rubber letters (such a great tool) were used to press the names of the flowers and trees into the tiles, effectively making these artworks into a visual field guide when installed altogether on the school fence. No doubt that having OISE teacher candidates Clara Hoover and Elena Viazmina help out made the project that much easier! Using natural materials (like clay) and installing outdoors are just two of the strategies for growing art in schoolyards – check out my new article about this in Art Education Journal in July 2019.

Making the clay leaves

Clay leaves on the fence