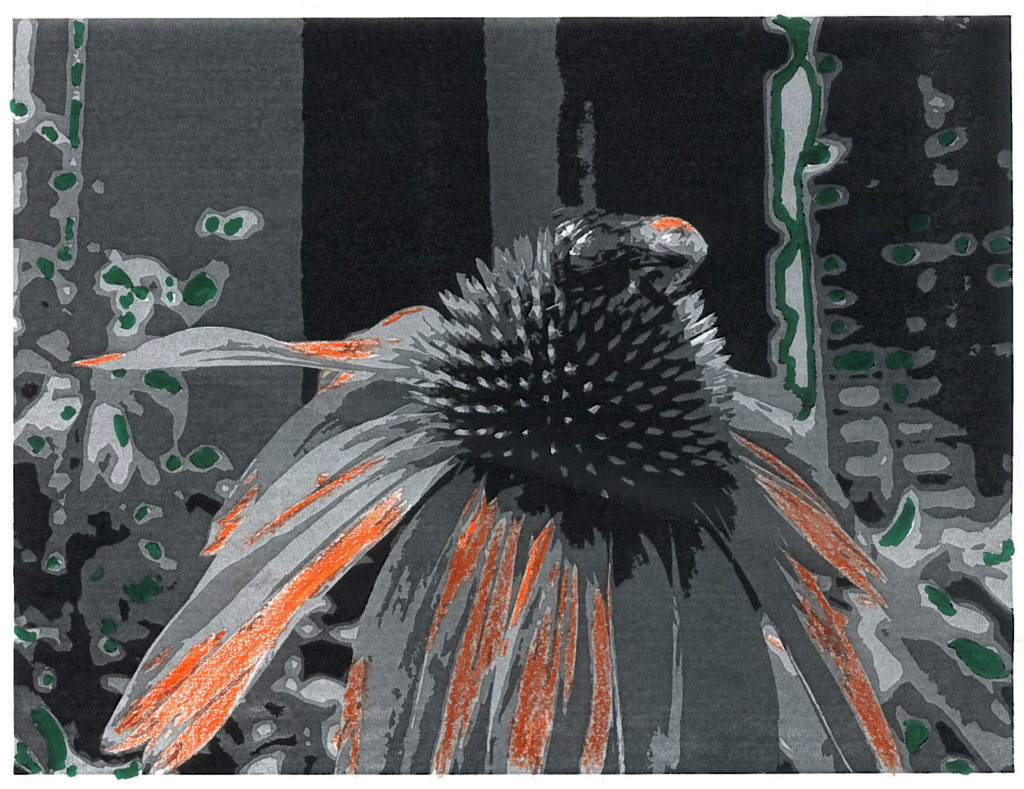

Happy to share a new study about eco-art education that our research team finished this fall. Recently published in the Journal of Art and Design Education (2020, vol 39, issue 3), this study explores the impacts of the environmental art installations Iãve been co-creating with students and faculty over the last decade at OISE, found in our walking art gallery. The article is entitled “Conceptualizing Art Education as Environmental Activism in Preservice Teacher Education”, and it draws on methods from arts-based research and qualitative case study in its investigation of the impacts of creating environmental art installations in a community-based, eco-art education program. Our findings support our lived experience that graduate students experienced behavioural and attitudinal shifts towards sustainability after engaging in the processes of creating environmental art; involvement in the program also provided opportunities for building community, engaging multiple domains of learning, modelling sustainable art-making practices, and prompting environmental activism. The results of this study ã along with the cover photo of one of our recent installations – continue to inform a developing pedagogy for environmental art education in higher education settings. My hope is that it inspires others to try eco-art ed in their own institutions.

ô ô

ô ô  ô ô ô ô ô ô

ô ô ô ô ô ô