Iãve been learning more about regenerative sustainability recently from my colleague John Robinson, who has been a vocal advocate for it at the University of Toronto in recent years (and at UBC for many years before that).ô This is built on the premise that itãs not enough to create communities that are ãnet zeroã in terms of their greenhouse gas emissions, but in fact are ãnet positiveã by actively contributing to a more sustainable world.ô John introduced me to this through the Centre for Interactive Research on Sustainability at UBC, (a building he helped design; it sends rain water used to flush toilets in the building back into the sewer cleaner than it arrived).ô So Iãve been looking for examples of ãregenerative art-makingã, and realized that we have two excellent examples of this in permanent installations of this in Toronto.ô Noel Hardingãs ‘Elevated Wetlandsã (1999), recognized by many Torontonians for its prominent position along the DVP, was an early example of this. Using solar pumps, native plants and a recycled plastic substrate, Noel integrated science and art to model how an art installation can contribute to the cleansing of the Don River (known as one of Canadaãs most polluted rivers.) Jill Anholt picked up on this two decades later in her design for Sherbourne Common, a small park on Torontoãs waterfront.ô With a similar purpose in mind, Anholtãs design uses UV light, native plantings and a mesh screening system to cleanse storm-water run off before it goes into lake Ontario. Both artworks create inspiring, purposeful spaces that model regenerative sustainability in creative ways – we need more like these around the word!

Art as Regenerative Sustainability

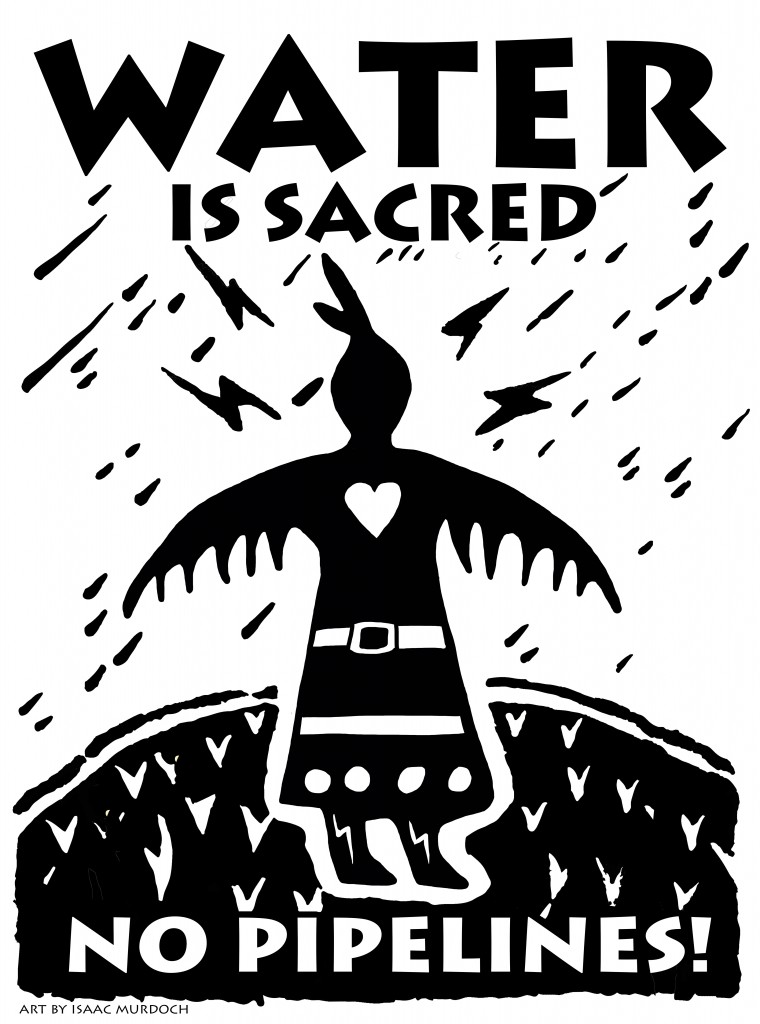

Learning from First Nations’ Artists

Are artworks created by First Nations artists a form of environmental art-making?ô Many can be considered as such, based on the imagery and meaning of their works; some draw attention to the natural world, are made with biodegradable materials, celebrate the interconnectedness of all forms of life and/or take an activist stance on environmental issues.ô I was honoured to learn from two artists who are well-known environmental activists here in Ontario – Christi Belcourt (Mûˋtis) and Isaac Murdoch (Ojibwe) (they were keynote speakers this year as part of our national conference in Environmental & Sustainability Education). They are the founders of the Onaman Collective, which focuses on a resurgence of First Nations language and Land-based practices. They have co-designed a series of graphic black and white images that draw on First Nations symbolism to support environmental activism, which they generously share for free with other activists.ô These small-scale, abstracted works sit in contrast to the huge colourful murals created by artist and traditional wisdom keeper Phil Cote (Potawatomi) around the city of Toronto; he leads the Tecumseh Collective. One series of his works is found on the edge of the Humber River, which feature the integral relationships between native riparian wildlife and First Nation peoples. ô All three of these artists take time to work in K-12 schools with children around the GTA and the province, generously sharing their knowledge of and commitment to the Land with the next generation, hopefully leading both Indigenous and settler children to live more lightly on the Earth.

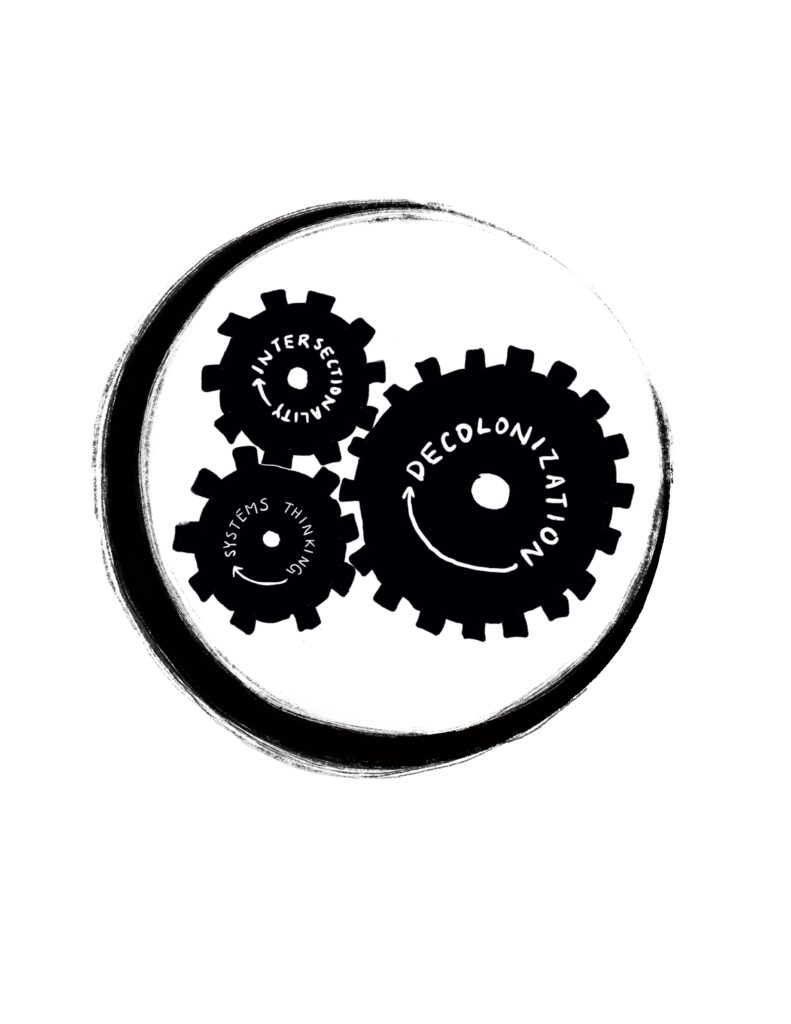

Keywords for a Just Recovery

We launched the 14th environmental art installation at OISE in February, and it signals a new approach.ô We havenãt been in our building at OISE for over a year, and we havenãt even been able to install last yearãs installation yet.ô So we thought weãd experiment with a digital installation this year, as everything else has moved online.ô A group of OISE grad students met with me online in the fall to brainstorm ideas for this yearãs project, which had to be simple enough in tools and technique that anyone could contribute an image to this collaborative, community-based artwork. We also felt it had to recognize the pandemic in some way, as this will be an era that will impact our lives for decades to come.ô I think we came up with a creative solution, entitled “Keywords for a Just Recovery.ã The installation was introduced via a webinar, highlighting how the pandemic has brought existing economic, social, and racial injustices to the fore, and how returning to ãnormalã was not an option. We explored the work of artists who have focused on notions of a ãjust recoveryã in recent months ã Jhon Cortes, Ricardo Levins Morales, Corrina Keeling, and Mona Caron, to name just a few, as well as examining the work of some artists who have led the way in working towards social and ecojustice justice for decades, like Krzysztof Wodiczko. OISE community members were invited to contribute an image (with a few keywords) that captures what they believe to be central to a ãjust recoveryã. I’ve really enjoyed working with Ashley Sikorski, one of our talented grad students, on this project (the images above are hers). The work is still in process, and with luck, will result in a digital installation later in the spring, and realized in physical form when our building re-opens.

How will you contribute to a ‘just recovery’?

Eco-learning to E-learning through Nature Journaling

Like so many things over the past few months, my blog writing has been sidelined since the arrival of the pandemic in Canada in March.ô I’ve been working on how to take an active PD series focused on environmental and sustainability education and shift it quickly to e-learning. Weãve been using the Zoom platform to bring EcoSchools teachers together with some success, as we’ve had more teachers involved than ever before. But my next challenge – how to do this with environmental art-making? The limitations have been daunting – the weather outside was wet and chilly, teachers were only able to join online, with no guarantees of specific art materials or tools on hand. But spring always brings with it a sense of excitement and anticipation in a cold climate, so turning our attention to nature-journaling seemed like a viable way to re-connect with other living beings in a time when we were mostly staying inside. I had great models to follow ã check out the amazing work of Clare Walker Leslie, or that of John Muir Laws and Emily Lygren ã artists who have written inspiring books on nature journaling for teachers to follow. I discovered that nature journaling can be framed through the 4Rs ã reconnect with nature, record nature, research nature, and reflect on nature ã and can be easily integrated with math, literacy, geography, and science. Its flexibility can allow for teachers and students to use any art materials at hand, putting their creativity into play as they learn about ecology, biodiversity, and climate change.ô Most importantly, the process of nature journaling can remind us that we are part of nature, not separate from it. If youãd like to experience this webinar, you can find it in the TDSB’s archive.

John Muir Laws & Emily Lygren

Clare Walker Leslie

Aligning the (Eco-Art) Medium with the Message

Remember McLuhan’s famous quote about aligning the medium with the message? He wrote this in the 1960s, well before environmental art-making became so popular, but it’s a good reminder for those of us practicing eco-art ed with learners of all ages. It’s not sufficient to be making art with a sustainability message if the media you use doesn’t align with it. Working with toxic materials like spray paint or oil-based paints subverts the very message we aim to communicate, and demonstrates a “do what I say, not what I do” attitude. Our students are attuned to this type of hypocrisy, and know when we don’t ‘walk the talk’. Art educators need to lead by example, finding ways to share our ideas in low impact, sustainable approaches to art-making. Some make work with their students that is biodegradable (think Andy Goldsworthy as an exemplar); others reuse found materials (Louise Nevelson was an early adopter of this; Tony Cragg also uses it effectively.) I hear of lots of art teachers experimenting with low impact art-making techniques, like gelatin printing and cyanotypes. Others are minimizing their waste and reducing their energy consumption and capturing the waste water from acrylic painting. If you’re looking for ideas on how to proceed, look to the Karen Michel’s book “The Green Guide for Artists” as a great starting point. Consider how can you take the next step in aligning your sustainability message with the media you use in your art classroom.

Eco-ARTS Education is on the Rise

Iãm really pleased to see that environmental ideas are infiltrating across the arts these days.ô When I first started to research into eco-art education, I was hard-pressed to find examples of drama, dance or music educators taking up the challenge of integrating environmental literacy into the work they did.ô Iãm sure it likely was happening in some pockets, like in visual arts education, but it wasnãt being documented or researched perhaps at the same level.ô This wasnãt due simply to a lack of professional exemplars; here in Canada weãve had many professional musicians, like R. Murray Schafer,ô Bruce Cockburn and Sarah Harmer using their music to connect to nature-based learning and environmental advocacy.

This is spreading, as artists from all of the arts disciplines are more frequently contributing their unique skills to raising awareness about environmental issues in plays, dance performances, and music videos.ô Here in Toronto we have the Broadleaf Theatre company that specializes in plays with environmental themes; their recent show The Chemical Valley Project tracks the deep challenges of environmental racism and colonialism in relation to Canadaãs petrochemical industry.ô And now thereãs lots of evidence that arts educators around the world are taking up the challenge of doing this work at all levels of education. ô I was happy to work with colleagues in the US and Australia on a chapter in a terrific book called Urban Environmental Education Review last year on this topic.ô And I was honoured this week to address a group of educators on this topic at the NORDPLUS Horizontal Green Actions conference in Finland; they had come together from Greenland, Iceland, Denmark, Norway, and Latvia to discuss, debate, and share promising practices in this area (thanks to David Yoken for the invitation!)ô Maybe we have reached a tipping point in the arts ã imagine what could happen if we all applied our creativity and innovation to the greatest environmental challenges of our times?

This is spreading, as artists from all of the arts disciplines are more frequently contributing their unique skills to raising awareness about environmental issues in plays, dance performances, and music videos.ô Here in Toronto we have the Broadleaf Theatre company that specializes in plays with environmental themes; their recent show The Chemical Valley Project tracks the deep challenges of environmental racism and colonialism in relation to Canadaãs petrochemical industry.ô And now thereãs lots of evidence that arts educators around the world are taking up the challenge of doing this work at all levels of education. ô I was happy to work with colleagues in the US and Australia on a chapter in a terrific book called Urban Environmental Education Review last year on this topic.ô And I was honoured this week to address a group of educators on this topic at the NORDPLUS Horizontal Green Actions conference in Finland; they had come together from Greenland, Iceland, Denmark, Norway, and Latvia to discuss, debate, and share promising practices in this area (thanks to David Yoken for the invitation!)ô Maybe we have reached a tipping point in the arts ã imagine what could happen if we all applied our creativity and innovation to the greatest environmental challenges of our times?

Inspired by Burning Ice

What a busy fall! ô Not as much time to blog as I would have liked following my trip to the Arctic this summer, but the trip has given me lots to think about in relation to climate change and the role that artists can play in addressing it. ô This was furthered by listening to a talk by Nigel Roulet in October – he is an eminent Canadian environmental scientist from McGill university who shared his belief in the power of the arts to communicate environmental ideas in moving ways, something that science hasn’t typically done well in the past. ô

Perhaps the best way to magnify the communications about climate change is to take a multi-faceted approach. ô The Cape Farewell project is one of the best examples of this so far; by bringing environmental scientists together with artists, musicians, writers and filmmakers, aiming to create innovative ways to reach a wider audience about the impacts of climate change. ô Their interdisciplinary book, called Burning Ice: Art and Climate Change, serves as travelogue, atlas, art catalogue, and scientific documentation all in one. ô Other groups have experimented with this model, including Greenpeace andô 350.org, bringing scientific knowledge together with the affective and intuitive ways of knowing from the arts to create memorable and moving messaging about climate change. ô The Canada C3 expedition I was on last summer is aiming to do the same. ô They have a number of legacy projects on the go to share our collective experiences about climate change, reconciliation, and inclusion in the North; Iãll share these as they come available.

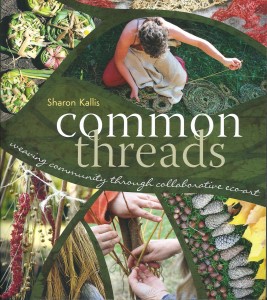

Collaborative Art-making in ‘Common Threads’

I attended a great talk on Eco-art recently by artist Sharon Kallis from Vancouver. She has authored a new book called ‘Common Threads’, which explores the use of collaborative art making as a way to raise awareness of the natural world and the environmental issues it faces. Invasive plant species are of particular concern, as she experiments with ways to re-purpose these plants as art material to deal with sustainability challenges. Sharon has created clothing out of plants, for example, weaving leaves and stems into functional material. I really enjoyed learning more about the community gardens she has been involved in in Vancouver, always with an eye on how the garden might be used as exhibition site or as a source for biodegradable art materials.ô ô Recently she has been growing flax to make into linen fibre, (demonstrating that she has far more patience than I do!) I really appreciate her use of art-making techniques with a rich history, and ones that have often been positioned as ‘women’s work’, helping to reclaim these into the lexicon of contemporary art practice. At the core of this work is always a focus on using art to build community, an important part of living more sustainably on the earth. More info about Sharon’s work can be found here:ô http://sharonkallis.com/

Creating Eco-Friendly Sculptural Books

While Iãve been busy with collaborative eco-art installations with my students this winter, summer always gives me a little more time to work on my personal artworks.ô Iãve been experimenting with sculptural book-making in recent years ã I love the combination of text and image, and the surprise of taking a traditionally flat object and making it come alive in three dimensions.ô So how do you make this technique more eco-friendly?ô Working with paper is a first step as it is easily biodegradable – that’s a natural when it comes to book-making.ô But Iãve also been drawing inspiration from a variety of sources, looking for ways to incorporate natural or found objects into my bookworks.ô I love the Spirit Books of Susan Kapuscinski Gaylord (http://www.susangaylord.com/the-spirit-books.html), who uses branches, grapevine and dried berries in this evocative book series.ô Mary Ellen Campbellãs books also incorporate a range of natural materials, often layering one on top of the other for a beautiful effect (find examples of her work on Pinterest.)ô Basi Irland takes a very different approach, freezing water and seeds into book forms that become part of a community performance as they float downstream (http://www.basiairland.com).ô If youãre looking for exemplars of how to re-use found objects and turn them into books, look no further than Terry Taylorãs EcoBooks: Inventive Projects from the Recycling Bin.ô Once youãve read this book, youãll be excited to try this yourself ã youãll be seeing possible books in everything you discard!

Using Digital Photos for Eco-Artmaking

Digital photography is a great technique to use for environmental art-making ã while itãs not ãno impactã (is anything?), it is low impact.ô For a small amount of electricity students can have so much fun taking photos and then modifying them in so many ways; itãs a great form of recycling!ô I have been using the work of many of environmental photographer/artists in my classroom as starting points for eco-art lessons.ô Canadian Ed Burtynsky is known internationally for his large-scale photos of human impact on the earth; if you havenãt seen his documentary Manufactured Landscapes, it is excellent viewing.ô I havenãt seen his newest one, called Watermark, but reviews of it are also strong.ô (More about his work at http://www.edwardburtynsky.com/ )ô The work of American photographer Peter Menzel is often found in my classroom as well ã his series Hungry World and Material World are fascinating portraits of familiesã consumption around the world; not surprisingly there are great disparities depending on where they live.ô I use his work to introduce eco-justice education and the power of art to raise awareness about inequity and its relationship to the environment.ô (http://www.menzelphoto.com/books/hp.php )ô And finally the work of American Chris Jordan (http://www.chrisjordan.com/gallery/rtn/#silent-spring ) is also useful to introduce how environmental statistics can have a greater impact when given visual form.ô ô Weãre experimenting with photography ourselves at OISE this summer by running a photography contest on our Learning garden – Iãll share the results in a future blog post.